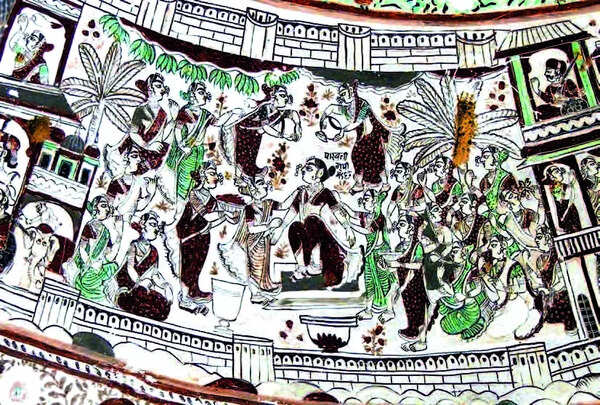

Inside the Kashi Vishwanath Mahadev temple, located on the banks of the Narmada in Chandod, Vadodara, visitors pause in silent reverence. Heads tilted skyward, they are transfixed by its magnificent dome — a 25-foot diameter masterpiece believed to have been created during the 18th century

Maratha rule. This arresting work of art showcases intricate multilayered paintings featuring 23 manifestations of the

Devi alongside vivid scenes from the

Ramayana.

“But what makes this place unique is its exceptional portrayal of Ravana’s army wielding guns and cannons. This represents the artists’ ability to incorporate contemporary elements into mythological narratives — even finding space to weave in popular 17th-century folklore like Dhola Maru,” says Pradip

Zaveri, who has meticulously documented

Gujarat’s murals, frescos and wall paintings over two decades.

Zaveri co-authored the newly released book, ‘Fading Treasure of Gujarat’s Wall Paintings’ (Gujarati: Gujarat no Visarato Bhintchitro no Kalavaibhav), published by

Kalatirth Trust. His fellow author, Purvi Goswami, brings her expertise in the Kutch region’s artistry to the collaboration.

The book traces the history and evolution of wall paintings across Gujarat, examining materials, themes and regions where they remain preserved. The authors identify Kutch, Mehsana, Gandhinagar, Panchmahal, Vadodara, Narmada, Bharuch, and Bhavnagar as the districts with significant collections of these preserved murals.

“The origin of the murals can be traced to long-standing traditions of the pothi chitra used in manuscripts in regions like Gujarat and Rajasthan. Of course, India has a long tradition of murals from places such as Ajanta Caves, but when it comes to modern murals in the context of Gujarat, we see the majority of examples from the Maratha era (17th-18th centuries). Compared to the finer style of Rajasthan, centred around the Shekhawati region, thanks to Pichhwai art, one may find examples from Gujarat relatively less evolved,” says Zaveri.

“But the works found in Gujarat possess their own visual grammar and distinct style.” The authors observe that most murals feature religious motifs — deities, celestial beings, epic scenes from Ramayana and

Mahabharata, historic battles and flora and fauna. Yet some pieces capture fascinating temporal contexts: Kheda houses murals depicting steam engines, while Gajera near Jambusar in Bharuch portrays European-administered capital punishment and Indian women serving European colonisers.

For history buffs, depictions of contemporary attire and customs in these murals shed light on specific eras. Since most works lack dating, experts determine their age through contextual clues — deities portrayed in period-specific styles, horses and palanquins with characteristic adornments, distinctive headgear, women’s attire, weaponry and other cultural markers.

Ramnik Zapadia, Kalatirth Trust trustee, said that few attempts have been made to document the state’s rich mural heritage. “Throughout the state’s diverse regions, we have found varied expressions of wall art that began as temple and residential embellishments before evolving into artistic expressions. Through this book, we intend to galvanize the artistic community and society at large towards preserving this rapidly vanishing cultural legacy,” he says.

A peek into the treasure trove

Tambekar Wada | Vadodara

This former residence of a Baroda state diwan (1849-1854) showcases some of the finest murals from central Gujarat. Its wooden surfaces feature celestial maidens, flora and fauna, reflecting both Indian and European sensibilities, Hindu deities inspired by miniature painting traditions and dramatic scenes from the 1802 battle between Maratha-English allied forces and the Arabs.

Sarveshwar Mahadev | Bhilapur

Some of the well-preserved murals in the temple are inspired by Kalidasa’s Kumara Sambhavam. The themes of other murals are inspired by Vishnu Purana, Shiv Purana, Dashavatara and Ramayana. The highly evocative style is primarily inspired by the Maratha school of painting.

Kashi Vishwanath Mahadev | Chandod

This 18th-century temple’s murals present a remarkable pantheon of Indian goddesses, including forms such as Wagheshwari, Shitala, Tulja and Momai Devi. Created using just five mineral pigments — including geru for orange, mineral-derived green and smoke-produced black — these works display distinctly Rajasthani stylistic influences.

Darbar Gadh | Shihor

Created using sophisticated tempera techniques circa 1790, these wall paintings dramatically chronicle the Battle of Chital. Experts believe the original watercolour compositions were subtly enhanced with oil paints during the 1940s.

Rughnathji Temple | Patan

This exceptional example of Gujarati mural artistry, dating to approximately 1840, features distinctive astronomical themes executed in the Kamangar painting style. Visitors can observe various planetary deities aboard their vehicles — Mars (Mangal) in a bullock cart and Jupiter (Guru) commanding an elephant-drawn chariot.

Swaminarayan Temple | Vadtal

Constructed between 1820 and 1823, during Sahajanand Swami’s lifetime, this temple displays murals depicting events from the Mahabharata and Puranas. Notable Salati-style paintings include scenes featuring foreign dignitaries, diplomatic meetings and military processions.

Wall paintings | Gajera

The exterior walls of these residences, estimated to be over 150 years old, feature rare depictions of railway carriages and British colonial execution practices. The Salati style paintings are present in four of the major wooden havelis of the village along with a few residences on Kanva road. Many of these paintings have faded and are now facing wear and tear due to its location.

Science of the arts

The authors explain that Gujarat’s murals predominantly employ tempera techniques, combining pigments with water-soluble binders such as egg yolk. The artists often prepared surfaces using conch powder or gypsum mixed with lime and sand. Lime underwent extended water immersion before being ground with neem gum and urad dal to create the application mixture. The walls were often kept moist for days before they were painted.Artists utilized larger-than-standard brushes and derived colours from natural sources ranging from minerals to vegetable dyes. Gold and silver leaf pigments were reserved exclusively for temple decorations. This traditional methodology remained largely unchanged until German synthetic dyes arrived in the 19th century.

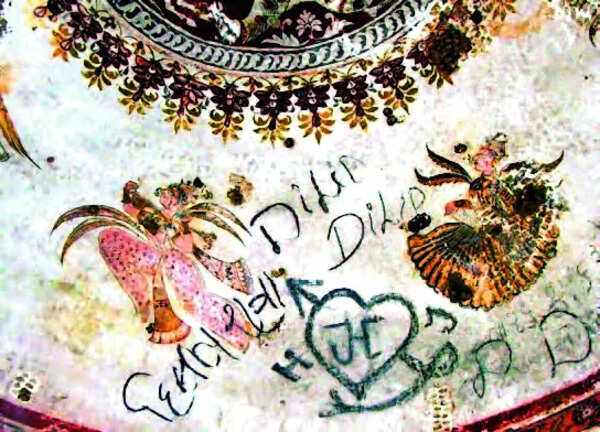

Preservation challenges

Experts identify both natural deterioration and human intervention as the primary threats to Gujarat’s mural heritage. Neglect and ownership changes frequently result in irreversible damage when murals are painted over. Environmental factors like vehicle emissions gradually erode lime layers and pigmentation. Misguided restoration attempts by inexperienced painters over the past half-century have sometimes disfigured original motifs due to inadequate technical understanding of historical surfaces and colours.Nevertheless, some preservation initiatives have been taken up by citizens to restore and conserve these artworks for posterity. In some cases, artists themselves have joined conservation efforts, including a dedicated couple in the Kutch region who are associated with notable restoration projects, according to Zaveri.

Experts also point at new electricity or water connections, seepage of water, repairs that may damage the wall as some of the reasons some priceless murals are now lost forever. Hamfeshwar Mahadev temple’s old murals are now lost forever after the construction of a dam. Attempts are now on to at least document the murals.